UK waste exports: A missed opportunity?

Most people are unaware that the UK exports over 10 million tonnes of waste each year, representing approximately 5% of all waste generated.

The biggest contributors to these exports are plastics, metal scraps, refuse-derived fuels, and electronic waste.

While it may seem that the UK is simply offloading its waste elsewhere (a practice that sometimes does occur), this export approach also drains valuable resources that could otherwise serve as fuel or raw materials, potentially boosting the UK’s economic output and enhancing its environmental standing.

This guide provides an in-depth analysis of UK waste exports. These are the key takeaways:

- Why export? It’s cheaper to outsource difficult waste management, and sometimes necessary.

- A waste of resources: Other nations get paid to receive plastics and refuse-derived fuels at the UK’s expense.

- Environmental implications: Unfortunately, a small portion of the UK’s waste stream leaks into the wrong hands, wreaking environmental havoc.

Why does the UK export waste?

Exporting waste seems like a total waste of shipping capacity. Except when you look at it through the lens of a commodity that, at best, can be recycled into new material and, at worst, replace fossil fuels as combustible energy.

Economics

Waste management in the UK is costly. Labour is expensive, landfill space is limited, disposal fees are high, and the landfill tax is rising. For instance, disposing of difficult-to-recycle materials via landfill can cost as much as £100 per tonne in the UK – significantly higher than in countries such as Turkey or Poland.

As a result, when waste management firms find it more economical and practical to export, they will do so as long as they can keep costs down while meeting stringent waste export regulations.

Infrastructure

Although the UK has substantial infrastructure for waste management, it cannot process all types of waste domestically, particularly certain types of hard-to-recycle plastics and electronic waste, which grow in volume annually. This leaves exports as the only way of meeting recycling goals, and no business or council wants to be seen falling behind.

Regulations

The UK is known for its strict environmental standards and commercial waste regulations, which make waste management more expensive. While cost is a big factor, regulations add another layer of complexity as they constantly evolve.

For example, China banned the import of plastic in 2018, leaving UK waste exporters scrambling for similarly priced alternatives in Asia and the EU.

UK waste export regulations

The Waste Shipments Regulation EC No 1013/2006 and its post-Brexit amendments (2019, 2020, and 2021) outline the rules governing waste exports. Here’s a summary of the key regulations:

- Waste exports must be correctly classified and comply with specific controls based on the type of waste, its intended treatment, and its destination.

- Waste can only be exported for recovery or recycling purposes, and none may be landfilled or dumped. In other words, it must be exported as a commodity.

- Exporters are required to ensure legal compliance, arrange financial guarantees, and manage waste shipments responsibly to avoid penalties.

What types of waste does the UK export?

We estimate that The UK generates over 200 million tonnes of waste annually (the last official statistics date to 2018), of which around 10 million (~5%) are exported to be managed abroad. This is mainly in the form of:

- Plastic waste (~600,000 tonnes)

- Refuse-derived fuels (~1,600,000 tonnes)

- Metal scraps (~8,200,000 tonnes)

- Electronic and electrical waste (~37,000 tonnes)

- Illegal waste exports (+30,000 tonnes)

Plastic waste exports

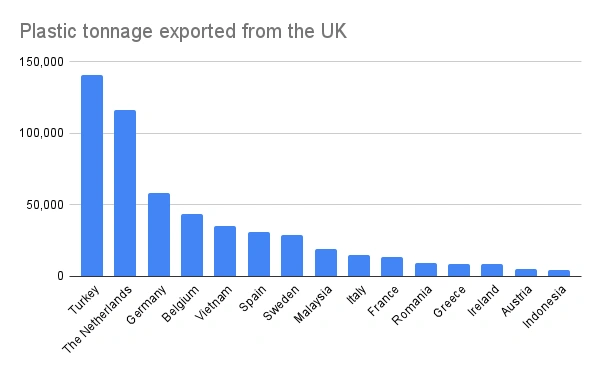

According to UK gov data, the UK exported 600,000 tonnes of plastic waste in 2023, or about 60% of the total plastic waste generated. This huge proportion has been steadily growing, partly why UK recycling rates have been increasing without significant investment in recycling infrastructure.

While the majority is managed within the EU, which has robust environmental regulations, around one-third ends up in developing countries like Turkey, Vietnam and Indonesia.

Plastic waste exports leave from Britain’s largest ports including Liverpool, Southampton and Newcastle.

Why is plastic waste being exported?

It comes down to high costs at home and a lack of commercial recycling technology.

While standard PET and HDPE are largely recycled in the UK, the difficult-to-recycle portion comprising most of the exported stream includes polystyrene, PVC, and composites.

This is because of a lack of proven technology to process these economically at scale (and the UK is not at the forefront of these developments), leaving recovery (i.e., incinerators) or landfilling as the only alternatives.

These bottom-tiered waste management activities are more competitive abroad, partly because of relatively high costs in the UK.

There is also demand for these problematic plastics abroad. They can be very cost-effective for energy-from-waste plants, cement manufacturers, and other heavy industries, as they are essentially getting paid to receive free fuel.

Something you won’t hear often is that plastics are essentially hydrocarbons in solid form and with greener credentials. This is because they are given secondary use when ‘recovered’ as fuels while avoiding their accidental release as litter into the natural environment.

Additionally, some foreign governments, like Poland’s, will support their industries for the sake of their own coffers, as these imports can be a valuable source of foreign exchange.

What are the issues of plastic waste exports?

The issue arises when the countries receiving it can’t effectively recover the plastic waste, potentially causing dire environmental issues. This is not a major issue in the EU but in other jurisdictions.

For example, there is extensive journalistic evidence (e.g., Bloomberg, BBC, Greenpeace) showing how a portion of the exported plastic wastes from the UK are illegally dumped or burnt in open fires in Turkey, causing extensive damage to the environment and humans, usually immigrants and refugees living in precarious conditions.

These scandals have led many to call for a ban on UK plastic exports. While this could benefit domestic incinerator businesses, UK companies would likely face higher commercial waste collection costs.

Refuse-Derived Fuel (RDF)

Refuse-derived fuel (RDF) is a product made from an assorted mix of combustible materials found in municipal and industrial wastes that is used to power Energy-from-Waste (incinerators).

It is produced by sorting refuse wastes until most recyclables and non-combustible materials have been removed, leaving only shredded combustibles like hard-to-recycle plastics, commercial food waste, spoiled cardboard and textiles, etc, that burn efficiently to produce energy.

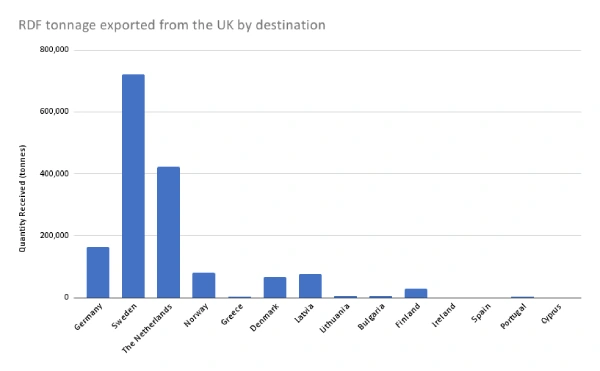

1.6 million tonnes of this refuse-derived fuel were exported from the UK in 2023, mainly to European countries like Sweden and Germany, which require large amounts of heat to keep their populations warm during their long winters. This represents a +500% increase since 2017, when only 290,000 tonnes of RFDs were exported, highlighting the UK’s lack of domestic waste management infrastructure.

Why have RDF exports increased so much?

Similar to plastic waste exports, it comes down to a lack of incinerating capacity, inferior technology, and simple economics.

Firstly, The UK’s generation of RDFs sometimes exceeds the capacity of domestic incinerators, leaving producers without storage capabilities with no choice but to export it. Some have even established long-term contracts and relationships to ensure RDFs can be reliably disposed of.

Additionally, the colder Nordic countries have invested in high-tech waste-to-energy plants for district heating, heavy industry, and electricity production, which are extremely efficient at burning RFDs. These plants inevitably have a competitive advantage over the UK’s domestic incinerators, as they can get more energy and fewer emissions from the same RDF tonnage.

This is especially true as domestic waste tonnages in Nordic countries have been dwindling due to improving recycling rates and changing consumption habits.

This is an example of how the UK is missing out on the benefits of a circular economy and the opportunity to ‘recover’ cheap energy from its most calorific waste.

Metal scrap exports

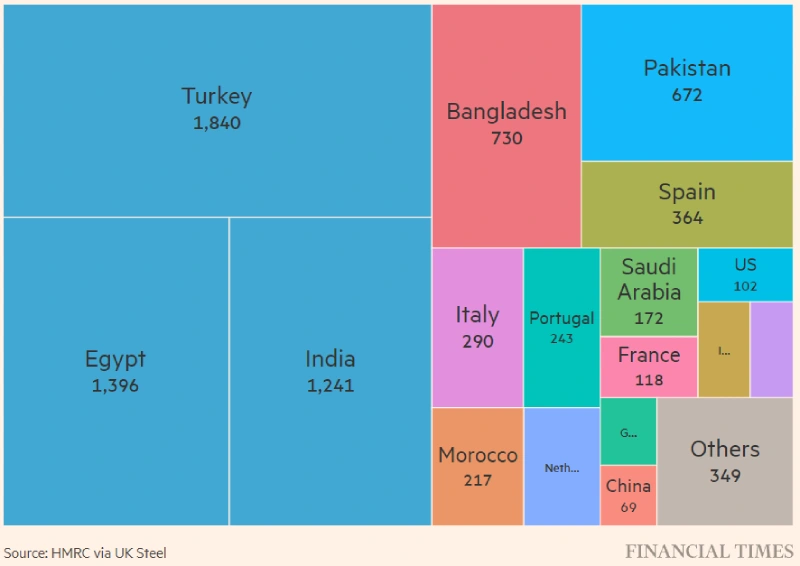

The UK is a major metal scrap exporter. In 2022, scrap companies sold around 80% of the metal scraps generated domestically (8.2 out of 10.6 million tonnes) to brokers and resellers abroad, bringing in millions of pounds to the UK economy each year.

In 2022, over half of this scrap metal was destined for Turkey, Egypt, and India, with the majority destined for steel production.

Why does the UK export the majority of its scrap metal?

According to this article, the UK’s lack of domestic demand is the main reason for its huge exports.

The UK generates a significant amount of metal scraps from end-of-life vehicles, construction waste and the decommissioning of oil and gas infrastructure, with few domestic smelters able to process it into steel and other metal products.

This domestic demand will likely remain low because the resurrection of steelworks is not high on the UK’s priority list. On the other hand, the global demand for metal scraps is expected to increase due to increasing mining costs and the rise of the Electric-Arc Furnace (EAF).

This high-temperature technology is cleaner because it uses electricity instead of the combustion of fossil fuels and is particularly advantageous to commercial metal recycling because it can melt 100% of the scrap, as opposed to traditional blast furnaces, which can only melt about 30%.

Only Tata Steel’s Polt Talbot smelter in the UK will be fitted with an EAF, leaving increasing metal scrap exports as the sole likely outcome.

Electronic waste exports

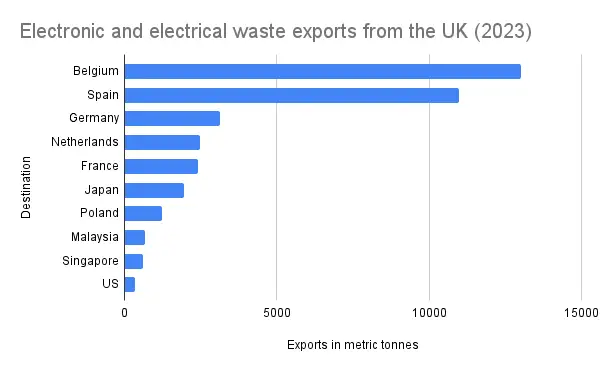

The UK exported over 37,100 metric tonnes of electrical and electronic waste in 2023, and this number is growing year-on-year due to the rapid digitisation of the economy.

Belgian and Spanish recyclers are receiving the bulk of this waste, with the rest divided amongst other EU countries like Germany, Netherlands, France, as well as other non-EU destinations, including Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, and the US.

This waste is received by recycling centres that carefully sort the valuable materials from the wastes (e.g. plastics) and then either smelt it in-house or re-export the sorted metals for smelting elsewhere.

Why is exporting electronic waste so attractive?

Because it’s profitable and the UK lacks the necessary recycling infrastructure.

New regulations mandate that electronics and electrical equipment retailers must receive waste electronics for repair or recycling, and sometimes, the lack of domestic capacity leaves them with no choice but to export a portion of it at lower prices.

💡 Electronic and electrical waste recycling can be very profitable due to their valuable metal contents.

Illegal waste exports

Criminals are profiting from illegal waste exports by shipping waste to locations that cannot safely process it.

A Financial Times investigation reports that an additional 30,000 tonnes of electronic waste are illegally shipped from Britain each year, often smelted down by underpaid workers in developing countries.

According to the investigation, these illegal exports follow various pathways, primarily involving the mislabelling of waste as functional electronics in charity ‘donations’ or ‘auctions’ of used electronics to poorer countries, primarily in West Africa.

The Environment Agency is actively utilising waste export data from HMRC to identify and intercept illegal shipments before they leave the country.

Are waste exports a missed opportunity in the UK?

It’s strange to think that outsourcing waste is a bad thing, but in reality, most waste is a valuable commodity. At least as long as there is infrastructure to deal with it at scale.

Instead of using gas power stations, the UK could have its own fleet of high-tech Waste-to-Energy plants to support the growing network of intermittent renewables and simultaneously deal with the hardest-to-recycle waste. The UK has emphasised waste incineration in its policy but still finds itself the more expensive alternative than sending this waste abroad.

Instead of exporting its metal scrap to other countries for processing (already a lucrative endeavour), the UK could add value by supporting high-tech, ‘green’ smelters that can process the scrap in the UK and export recycled metals (e.g. Green Steel). The same applies to electronic waste that contains high concentrations of precious and other valuable metals.

Assuming its facilities can maintain high environmental standards, this could reduce the UK’s trade deficits and help the world curb its waste problems. It’s important to realise that despite its shortfalls, UK waste management is of much higher quality than in developing countries.

What are the economic benefits of UK waste exports?

Waste exports such as metal scraps and RDF are lucrative for exporters, bringing millions of pounds (or perhaps dollars) into the UK economy. The same applies to electronic and electrical waste, which contains metallic components that make it profitable for recyclers.

However, exporting plastics is a missed opportunity for the UK economy. Waste management firms sometimes pay other businesses to receive this waste despite its great value as fuel for energy-from-waste plants.

While this might help businesses reduce their commercial waste collection bills (as incinerating or landfilling these hard-to-recycle wastes is more expensive in the UK), it is literally transferring value abroad.

What are the environmental impacts of UK waste exports?

Besides the carbon emissions and water pollution associated with waste shipments, there are plenty of environmental concerns, especially from wastes that are exported both legally and illegally to developing countries because of their lower level of regulations and compliance with environmental and waste regulations.

For example, significant journalistic evidence points to the illegal burning and disposal of plastic waste that is legally exported to Turkey, and well-known locations in West Africa are known for dangerously processing electronic waste from Europe and the UK.

The environmental consequences of these practices are dire, including polluting air, water and soil with toxic chemicals released from both plastics and hazardous electronics. Also, plastic waste that is released into the environment does not degrade easily and will damage ecosystems. This includes the production of microplastics that eventually end up in the human food chain.

For a more detailed response, read our breakdown of the different types of waste exports and our bespoke article on the environmental impacts of commercial waste.