Are incinerators the future of waste management?

The UK government has clear targets to increase recycling and reduce landfilling, yet there has been limited discussion regarding incinerators.

While some argue that they are key to reducing landfill waste, avoiding emissions and generating energy, others point out – often more robustly- that they do more harm than good. Incinerators increase emissions and ultimately discourage local councils from improving recycling rates.

In this article, we give you the good, the bad, and the ugly of UK incinerators.

💡 Key takeaways:

- Incineration: The burning of waste reduces volumes by 90% and recovers energy and valuable ash.

- UK incinerators: There are 55 incinerators in the UK, of which the vast majority are in England.

- Discourages recycling: Unfortunately, incineration contracts are long and penalise councils for not meeting their waste quotas. The consequence is that reducing waste through recycling results in expensive fees for the government.

What is an incinerator?

Put simply, an incinerator is any facility that burns waste at high temperatures to reduce its volume. This process produces ash, gas, and heat as byproducts.

The heat generated from the chemical reactions can be transferred elsewhere via water/steam for useful heating or generating electricity.

The remaining ash usually contains valuable non-volatile materials like metals in high concentrations that can be recycled.

Gas emissions are usually laden with toxic gases, particulates, and carbon, which need to be filtered and cleaned to within legal limits before being released into the atmosphere.

Given the nature of incineration processes and emissions, these facilities are usually located in industrial areas and require a constant supply of various waste materials, including waste collected by the council, as well as industrial, clinical, and hazardous wastes. These are stored in bunkers before being sent for incineration.

The waste is incinerated in a specialised chamber, usually in the presence of oxygen (combustion), although some specialised incinerators for plastics or tyres do this in an air-free chamber (pyrolysis) in a process akin to the production of biochar.

💡Volume reduction: Waste volumes are typically reduced by 90% through incineration, reducing the strain on limited landfill space.

Waste-to-energy incinerators

Waste-to-energy (WtE or W2E) or Energy from waste (EfW) incinerators are equipped with energy recovery technology to harness heat or use it to turn a steam turbine and generate baseload electricity. These usually use water-based systems to transfer this energy around and put it to use.

Most incinerators in the UK are WtE, so both words are typically used interchangeably.

A brief history of incinerators

Incineration has existed for many thousand years, ever since humans settled and generated waste that needed discarding. Early examples include the burning of sewage and agricultural waste for nutrient-rich manure.

Industrial incinerators were a Victorian invention during the Industrial Revolution. The first incinerator, or “destructor,” was built in Nottingham, UK, in 1874.

One decade later, the invention was exported to the U.S., Europe and the rest of the world. The more a country industrialised, the more it could produce and the more waste it generated, starting a flywheel effect for landfills and incinerators.

While the original purpose was exclusively to reduce waste volumes and generate solid byproducts, the focus later shifted to recovering as much material and energy as possible and reducing emissions of greenhouse and toxic gasses and fine particulates.

💡 The Destructor: This first incinerator in Nottingham could burn around two to three tonnes of waste per day, helping the city reduce waste volume and prevent diseases that were rampant in industrialised cities in the UK.

Waste-to-energy incinerators in the UK

By December 2022, 55 Waste-to-energy plants were in operation in the UK (57 including British Crown Dependencies), and 18 were under construction or commissioning.

Here is the distribution of existing incinerators per location:

Their combined capacity is 23 million tonnes of waste per year, although only about 14 million tonnes are incinerated every year.

This list excludes cement kilns, clinical waste incinerators, biomass incinerators and power stations (like Drax Power Station).

Source: UKWIN

💡 Incinerators in major cities: Some of the UK’s biggest cities all now have local incinerators, including Skelton Grange in Leeds, Cutlers Gate in Sheffield and Marchwood in Southampton.

The growth of incineration in the UK

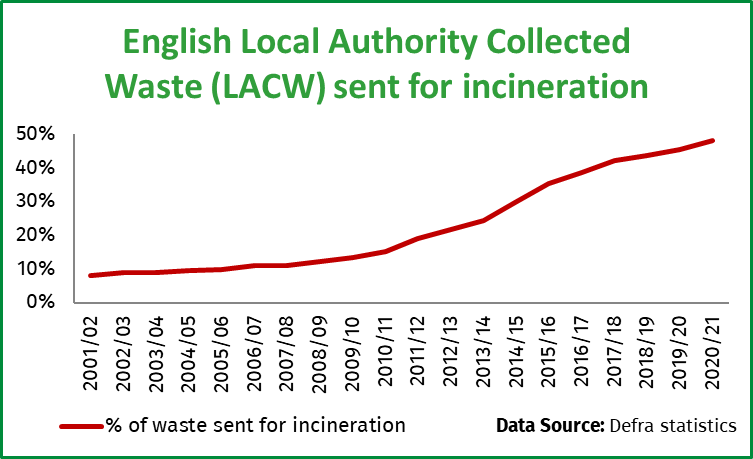

Since the start of the century, the amount of council waste generated in the UK has fallen by 8%, from 28 to 26 million tonnes, as commercial recycling and other waste minimisation and avoidance practices become more commonplace.

On the other hand, the proportion of incinerated waste has increased five-fold from 2.4 to 12.5 million tonnes, showing an increasing preference for this type of waste management during this period.

Which brings us to…

Why does the UK rely on incineration?

There are a few reasons why the UK has ended up prioritising incineration:

Landfill tax

The UK government implemented the landfill tax in the early 1990s to slow down the filling of landfill sites, which were rapidly reaching capacity, and to encourage waste minimisation and recycling. As a side effect, incineration became an economically attractive alternative to landfilling and recycling. It’s no coincidence that the growth of waste incineration is correlated with historical landfill tax rate hikes.

Public policy

Public policy considers waste-to-energy incinerators a source of green energy, providing electricity and heat from material that would otherwise end up landfilled. While an incinerator’s environmental credentials depend on its efficiency and the composition of the waste feed, the EU Directives inherited by the UK before Brexit promoted energy recovery from waste over landfilling.

As a result, waste-to-energy incineration remains embedded in the UK waste hierarchy (policy), where it is considered a priority over landfilling.

However, there’s been a recent shift into circular economy thinking, embodied by the latest Environmental Protection Act 2021. In this approach, incinerators are considered akin to landfilling. Data from UKWIN shows that over 100 new incinerators have been ‘prevented’ by public pressure in the UK in recent years.

💡Waste targets: By 2035, The UK expects to reduce municipal waste landfilling to less than 10% and recycling to 65%. There is, however, no fixed target for incineration, giving the government flexibility to burn more waste in case it cannot meet its recycling targets.

Waste density

London and some parts of the South East like Kent and Surrey are densely populated with homes and businesses generating large amounts of waste (i.e. the average UK citizen generates almost half a ton of waste yearly alone). Landfill siting is difficult in these populated regions, making incineration an attractive alternative to reduce unavoidable waste volumes and save precious landfill space.

💡 Incineration capital: As the densest area in the UK, London had the highest incineration rate (64%) and the lowest recycling rate (30%).

Are incinerators good or bad?

Now, to the crux of the issue.

Proponents and industry leaders champion waste-to-energy facilities as they ease pressure on landfill capacity and ultimately help recover some components of difficult-to-recycle items.

On the other hand, critics point out that, in practice, it is even dirtier and more carbon-intensive than landfilling and distracts from more useful processes like waste minimisation and recycling.

Cons of waste incineration

The charity UKWIN provides three well-researched and compelling reasons to reject this method of waste management:

1) Incineration harms recycling

According to numerous studies, a lot of the waste disposed of in general commercial waste bins (i.e. residual waste) is actually made of easily recyclable materials like commercial food waste, commercial cardboard recycling, commercial glass recycling. This is not surprising given the low proportion of businesses that are actually compliant with commercial waste regulations.

While we don’t have estimates for commercial waste collections, as much as 50% of domestic and municipal waste (which we can use as a proxy) is composed of easy recyclables, implying that much of the incinerated waste should actually be reused or recycled.

While it’s easy to blame councils for their lack of recycling, some of them are actually stuck between a rock and a hard place. having signed decade-long waste contracts with incinerators.

Since incinerators require a constant supply of waste feed (their primary fuel) to operate economically, their long-term contracts often include minimum tonnage guarantees, which penalise the council for not sending the agreed quantities.

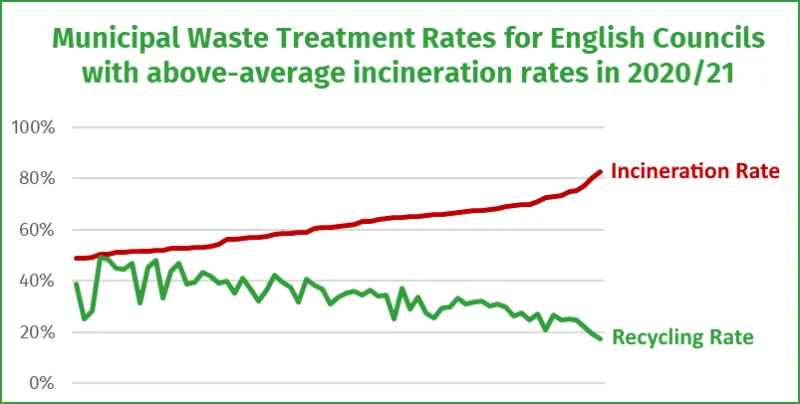

Naturally, this disincentivises councils from developing recycling, even if there is a change into a ‘green’ administration. This trend is reflected in the negative correlation between incineration and recycling rates. The more you incinerate, the less you recycle.

Fortunately, a reduction in the total amount of general waste generated in the UK and the growth of recycling are creating a surplus of incinerator capacity. This trend is expected to continue as councils are supported to meet the government’s target of 65% of all waste being recycled by 2035.

💡 Who ends up losing? The average taxpayer, of course. A chaotic, last-minute shift in waste management is always more expensive than a gradual, strategic shift. Any penalties levied on councils are ultimately going to be paid by a rise in council tax or by UK central bank inflation.

2) High greenhouse gas emissions and harming air quality

The process of incinerating waste material causes emissions. Generally, for every tonne of waste incinerated, a tonne of CO2 is released into the atmosphere, negatively contributing to climate change.

Popular opinion believes that since this is principally ‘residual’ or hazardous waste (at least on paper), this is an acceptable practice, especially given that recovering valuables from the remnant ash as well as energy in the form of heat and electricity makes this ‘circular’.

However, evidence suggests that, in practice, this is not true.

Firstly, around half of the incinerated waste is made of ‘fossil carbon’ (i.e. carbon that is already ‘locked’ in a stable, solid form, like in plastics). Landfilling or recycling this fossil carbon (i.e. plastics) and preventing it from reaching the atmosphere as a greenhouse gas is akin to doing Carbon Capture and Storage).

Secondly, evidence shows that English incinerators actually perform less efficiently than on paper and release significantly more emissions than initially foreseen. In 2020, the UK’s 55 incinerators released 14 million tonnes of CO2 at a carbon intensity of 600 – 800 tonnes of CO2 per kWh. This is worse than any other electricity-generating technology except for coal power, which the UK has banned.

Even when counting methane emissions from UK landfills (due to food waste and other organics erroneously ending up in municipal solid waste), incinerators are often doing comparatively worse.

Another issue is that burning a random assortment of wastes, including hazardous and toxic wastes, yields toxic gases, heavy metals, dioxins, and other particulates that can harm human health and the natural environment.

💡 Greenwashing: Waste-to-energy plants have been able to legally generate carbon credits despite the high carbon emissions associated with these plants due to ‘preventing’ methane from landfills. This is harmful to both the image of carbon financing and carbon emissions.

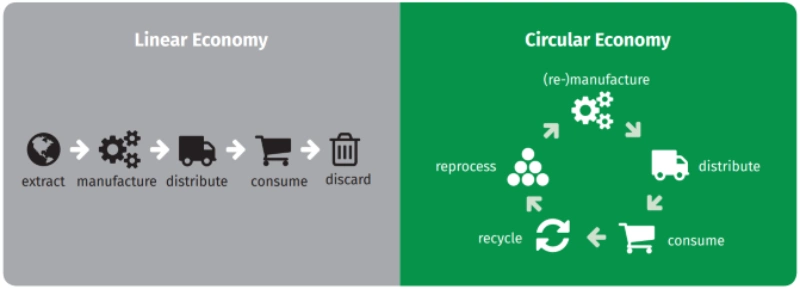

3) Incinerators are not ‘circular’

Some argue that incinerators are part of a circular economy because energy and valuable materials can be recovered from the ash and heat byproducts and put back into the system.

While this is true, if incinerators discourage recycling, it actually turns existing processes into a more linear economy. It’s the same as arguing how biofuels are cleaner than normal petrol but ultimately slow down the development of truly clean technologies like EVs.

Pros of waste incineration

1) Saves landfill space

The ‘residual’ general waste stream must be disposed of in a landfill or incinerated as it is, in theory, composed of non-recyclable or hazardous materials that are simply too dangerous to handle.

Ignoring changes in recycling and waste minimisation, reducing landfilled waste becomes as simple as incinerating more or exporting more. Generally, incinerating is cheaper.

In a way, waste-to-energy plants are less visually impactful than landfill sites and are, therefore, more acceptable. Would you rather have a well-disguised incinerator or a landfill site opposite your backyard?

So, while recycling and reusing remain the best ways to reduce landfilled waste, waste-to-energy is the easiest and an invaluable fallback until the infrastructure becomes appropriate.

💡 Landfill stats: The UK has 574 operational landfill sites and a spare capacity of about 200 million tonnes of waste. If 13 million tonnes of annually incinerated waste were sent to landfills instead, the UK would fill all its landfill sites twice as fast and reach its current capacity in 7 years instead of 14.

2) Generates baseload power

Waste-to-energy incinerators in the UK generated about 3% of the UK’s annual electricity in 2021. This may be a small contribution, but it acts as an important source of baseload power.

Baseload power is necessary to sustain the growth of renewable energy as large-scale energy storage facilities are being built, and having some waste-to-energy to support the network when the wind doesn’t blow or the sun doesn’t shine is valuable for The National Grid.

💡 Industrial energy: Since incinerators are typically located in industrial areas, any heat or energy recovered from the process can be used by neighbouring industries, reducing transmission inefficiencies. B2B private energy deals between industries are also possible, reducing any overhead.

3) Some valuables can be recovered

Incinerator ash often contains high concentrations of metals that can be recovered and recycled. These include ferrous metals (like iron and steel) and non-ferrous metals (such as aluminium and copper). Another portion of the same ash can be processed and used as a component in construction materials, such as aggregate in road construction or as a raw material in cement production.

While this is the lowest form of recycling, it is still a valuable way of keeping certain materials within systems.

The future of incineration

Given the recent shift into a fully circular economy, it is likely that waste-to-energy capacity will lose importance over time. As existing long-term contracts expire and general waste feed dwindles due to increased recycling, we are likely to see mass closures of incinerators in the future as they become uneconomical.

However, having some incinerator capacity will remain relevant for many decades as it is simply necessary to dispose of some unavoidable wastes. Think of contaminated needles and medical scalpels, bandages, asbestos, quarantine waste and some low-level radioactive wastes.

Therefore, we expect a large decline in incineration, but potentially never to zero capacity.

Incinerators – FAQs

Our business waste experts answer commonly asked questions on UK incinerators.

Do all incinerators in the UK generate electricity?

No. Not all incinerators in the UK generate electricity or heating, but many of them do. The trend in the UK has been towards integrating energy recovery into waste management, yet some older or small incinerators remain unequipped with these systems and solely focus on waste reduction.